- By:

- Category: Labor

POLICY REPORT: Expiration of Pandemic Jobless Programs Caused Unprecedented Drop in Access to Unemployment Insurance ![]()

TECHNICAL APPENDIX: Expiration of Pandemic Jobless Programs Caused Unprecedented Drop in Access to Unemployment Insurance ![]()

At the start of the pandemic, Congress temporarily expanded Unemployment Insurance (UI) programs through the federal CARES Act. This report mainly focuses on Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC), which expanded the weeks of UI eligibility. This and other emergency provisions were set to expire on September 4, 2021, which is commonly referred to as a “benefits cliff.” However, policymakers in some states chose to end these programs before that date. This policy report evaluates the impact the expansion and expiration of these programs had on the US labor market using data from the U.S. Department of Labor, the Current Population Survey, and California’s Employment Development Department.

The research found that the primary effect of the early turn offs was to lower the share of unemployed that receive unemployment checks, depriving jobless workers of financial assistance and limiting the ability of the UI program to bolster the economy. In contrast, the research found no appreciable increases in employment following the sharp benefit cutoffs. Also, the resulting decrease in the recipiency rate (the share of unemployed workers who are receiving UI benefits) was three times as large as a similar cliff at the end of the Great Recession.

Key Findings

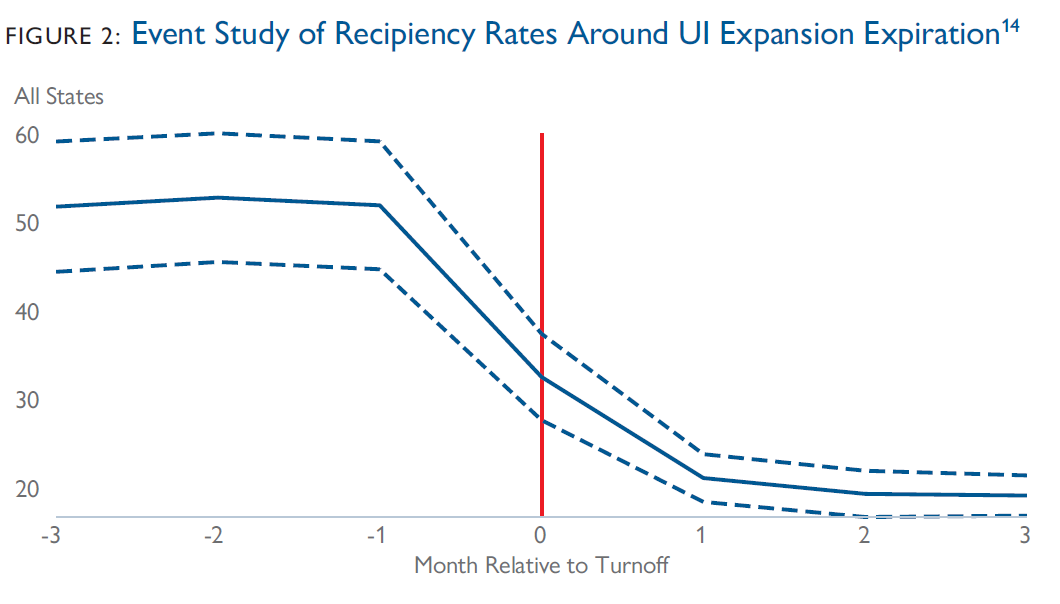

1. Access to UI fell drastically as a result of the benefits cliff. Prior to the turnoffs, about 50% of unemployed workers nationally were receiving UI benefits, but this rate declined to an average of around 20% two months after states’ turnoff dates.

Notes: This figure presents event studies of the recipiency rate around the time of withdrawal from UI expansions. The top panel displays the population-weighted mean recipiency rate for all states (excluding Louisiana) combined. The recipiency rates are combined relative to each state’s turnoff, meaning that -1 on the x-axis is averaging May recipiency rates from early turnoff states and August recipiency rates from normally scheduled turnoff states. Louisiana is excluded from all panels. The dotted lines represent the upper and lower bounds for the 95% confidence interval. (A version of this figure in the report includes two additional panels, breaking out early turnoff and normal turnoff states).

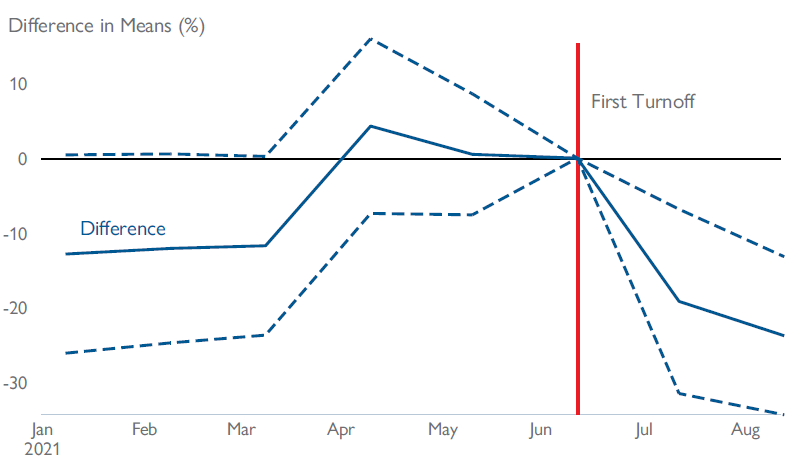

2. The drop in access showed up earlier in states that opted to end UI expansions earlier, underscoring the causal effect of the UI expansion in making benefits accessible. The two groups of states trended similarly in the months prior to early turn-off.

Figure 3: Trends in Recipiency Rates

Notes: In this figure, the difference between the population-weighted average recipiency for early and normally scheduled turnoff states (early minus normally scheduled turnoff) is shown relative to the difference in June, with the dashed lines representing the 95% confidence interval for this difference. Excludes Louisiana. (A version of this figure in the report includes an additional panel, showing the population-weighted average recipiency for early and normally scheduled turnoff states separately).

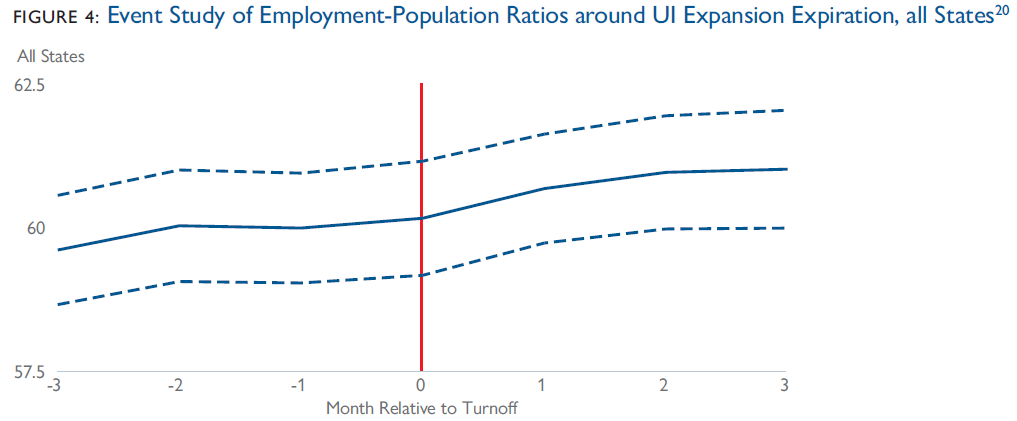

3. The expiration of benefits spurred little, if any, immediate return to work. There was no noticeable jump in employment at the benefit cliff. Even accounting for month-to-month variability, employment gains due to the expiration of benefits could not have been greater than half of a percentage point.

Notes: This figure presents event studies of the EPOP rate around the time of withdrawal from UI expansions. It displays the population-weighted mean EPOP rate for all states (excluding Louisiana) combined. The EPOP rates are combined relative to each state’s turnoff, meaning that -1 on the x-axis is averaging May EPOP rates from early turnoff states and August recipiency rates from normally scheduled turnoff states (excludes Louisiana). The dotted lines represent the upper and lower bounds for the 95% confidence interval. (A version of this figure in the report includes two additional panels, breaking out early turnoff and normal turnoff states).

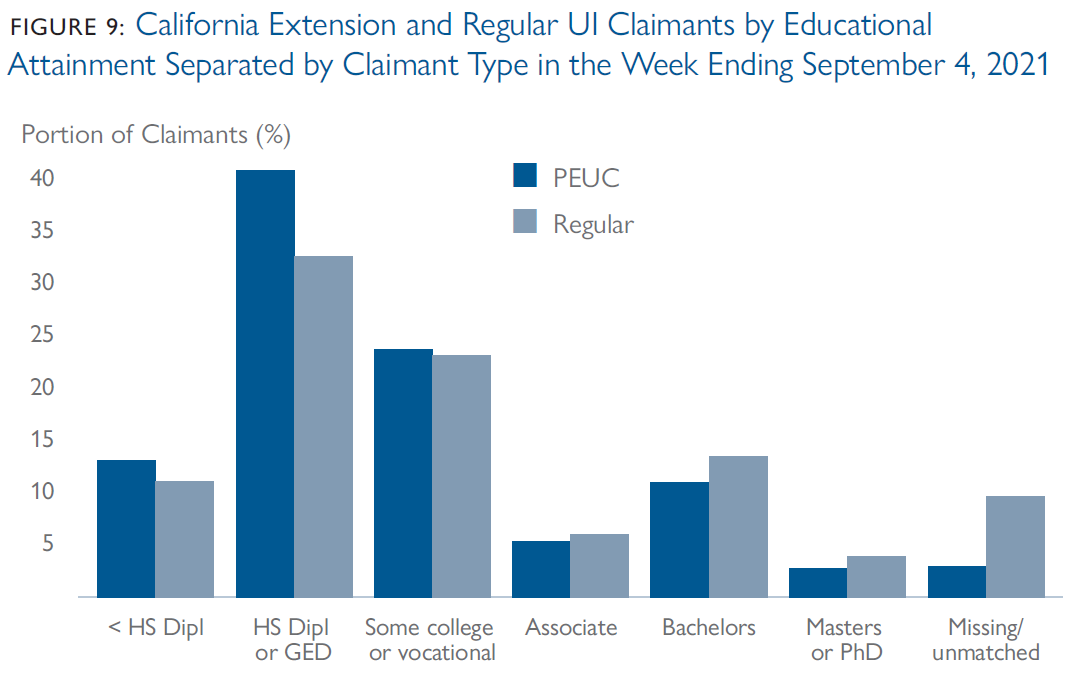

4. Already vulnerable workers were the most likely to be impacted when PEUC terminated in California, including women workers, less-educated workers, older workers, Black workers, and food and retail service workers.

Notes: Displays the proportion of claimants by highest degree obtained by claimant type. The bars add up to 100% for each claimant type. Educational data is collected by the Employment Development Department and is self-reported.